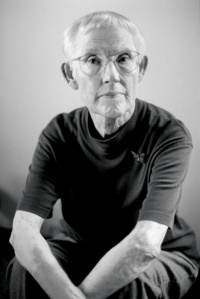

Charlotte Joko Beck was an American Zen teacher and the author of the books Everyday Zen: Love and Work and Nothing Special: Living Zen. “As you embrace the suffering of life, the wonder shows up at the same time. They go together.”—Charlotte Joko Beck In this collection of never-before published teachings by Charlotte Joko Beck, one of the most influential Western-born Zen teachers, she explores our “core beliefs”—the hidden, negative convictions we hold about ourselves that direct our thoughts and behavior. Joko Beck Charlotte Joko Beck (1917-2011) was a Dharma heir of Hakuyu Taizan Maezumi and also studied with Haku'un Yasutani and Soen Nakagawa. She established the Zen Center of San Diego in 1983 and was the author of Everyday Zen (1989) and Nothing Special (1993).

Charlotte Joko Beck, 81, started practicing Zen in the mid-sixties after raising four children on her own. She grew up in New Jersey, where she attended a Methodist church and “learned a lot of good quotes.” At Oberlin College, she studied piano, and later performed professionally “with little symphony orchestras—no big deal.” She supported her family by working as a schoolteacher, a secretary, and finally as an administrator in the chemistry department at the University of California, San Diego. When she retired in 1977, she went to live at the Zen Center of Los Angeles. In 1983, the Zen Center of San Diego opened—in two little houses, side by side, no sign—with Joko as teacher. She’s evolved her own way of teaching, which is always open to change. “I’ll pick up anything if it’s useful. It’s a question of seeing what really transforms human life. That’s what we’re interested in, isn’t it?” She’s just discovered Pilates, a form of exercise combining yoga, dance, and resistance training, and “probably I’m learning something there that will get mixed in, too.”

Charlotte Joko Beck Controversy

I had a fine life. I was divorced—my husband was mentally ill—but I had a nice man in my life. My kids were okay. I had a good job. And I used to wake up and say, “Is this all there is?”

Then I met Maezumi Roshi, who was a monk at the time. He was giving a talk in the Unitarian Church downtown. I was out for the evening with a friend, a woman, a sort of hard-boiled business type, and we decided to hear his talk. And as we went in, he bowed to each person and looked right at us. It was absolutely direct contact. When we sat down, my friend said to me, “What was that?” He wasn’t doing anything special—except, for once, somebody was paying attention.

Joko Beck Youtube

Charlotte Joko Beck (1917-2011) was a Dharma heir of Hakuyu Taizan Maezumi and also studied with Haku'un Yasutani and Soen Nakagawa. She established the Zen Center of San Diego in 1983 and was the author of Everyday Zen (1989) and Nothing Special (1993). It is no exaggeration to say her teaching transformed the nature of Zen in America, restoring a sense of emotional reality to a practice that all too often bypassed the “merely” psychological in the pursuit of realization. In a generation plagued by scandal, including the misconduct of her own teacher, she had the courage to challenge the traditional modes of teaching that failed to address the underlying character flaws. She made facing anger, anxiety, and self-centeredness central to our work on the cushion, examining how these marked the limits of our willingness to fully be present to the moment-by -moment truths of interconnectedness and impermanence. She taught us to find the Absolute in each moment regardless of its content, and not to turn practice into the pursuit of kensho experiences. Enlightenment, she taught, was the absence of something, not the added presence of some special experience. Being just this moment was compassion's way.

Left to right: David Mokusui Bruner, John Daido Loori, Charlotte Joko Beck, and Gerry Shishin Wick at the Zen Center of Los Angelesin the late 1970s. Photograph courtesy of Gerry Shishin Wick, Roshi

Joko Beck Husband

As one of the first Western women teachers, she attempted to free American Zen from many of the trappings of Japanese culture and patriarchy. She discontinued shaving her head, wearing formal robes or using Japanese titles. One of her great virtues as a teacher was that she did not try to clone herself. She let her own students and heirs digest her teaching and grow in their own different directions. Joko does not leave behind an institutional legacy. There is no central Ordinary Mind training center. There is no hierarchy among her Dharma heirs, no single voice that clearly continues her message. Her legacy is broad and cultural, a sea-change in how our generation thinks about the nature of practice and its relationship to our personal psychological make-up. Her Dharma seeds are scattered far and wide. They will go on sprouting in ways we cannot predict and cross-fertilize with other lineages. The Ordinary Mind School may grow or wither, but her influence is now everywhere.